There are lots of reasons to shift to more privacy-conscious business and marketing models, but the path can feel daunting. Privacy movements have been around for a long time, but businesses and marketers who choose privacy-respecting practices over surveillance are still early on the adoption curve.

However uncertain it might feel, businesses will soon have to start considering privacy more seriously. Why? Because there are several elements simultaneously converging that will push organisations towards more privacy-conscious approaches.

What are these elements?

General awareness about privacy, tracking and the harms of surveillance capitalism

Privacy pushes in tech, particularly from Apple

Industry awareness of how inaccurate data is

Ethical conflicts: the harms of tracking are often directly in conflict with an organisation’s stated mission

Privacy laws, especially in jurisdictions that recognise the harms of tracking

An ever-increasing range of software and services that place privacy at their core

These factors have varying levels of impact individually, but together they show a general trend that should encourage us all to take more privacy-respecting approaches.

1. Awareness

For many people, Cambridge Analytica and the 2016 Brexit referendum/US election were the first time the impact of online tracking could be truly felt in the offline world. But awareness in the general public is increasing every day.

In 2021 alone, two events drew significant attention to the impact of surveillance business models: the January 6th insurrection and the Facebook whistleblower, Frances Haugen. The wake of both events saw a great deal of attention in media columns, minutes and from lawmakers.

The Facebook Files highlighted that Facebook wasn’t nearly enough action on the known harms of their platforms. In just one example, Facebook’s own research suggested that the platform’s recommendation engine was responsible for radicalising 2/3rds of QAnon members.

The Check My Ads Institute has worked to show how adtech has funded the January 6th insurrectionists. YouTube played a role, too, as highlighted in the New York Time’s miniseries, Rabbit Hole.

Organisations like The Markup continue to raise awareness into the harms and widespread use of tracking through journalism and tools like Blacklight. They’ve uncovered how Facebook receives sensitive medical data from hospital websites and revealed how companies and lobbyists use adtech to maintain a positive image across the political spectrum, targeting specific ads to different political leanings.

Beyond this, privacy is even making it to TV ads. In a 2022 campaign, Apple highlights how data is auctioned:

DuckDuckGo also took aim at the tracking practices of Google in the same year:

Of course, this is marketing for these companies, but they wouldn’t be spending money on this if it wasn’t an angle that piqued the interest of potential customers.

And while we’re on DuckDuckGo, 2021 saw the privacy-focused search engine average over 100 million daily searches and growth of almost 47% in a single year.

2. Privacy pushes by Apple

As large and dominant as Google and Facebook are, their surveillance advertising business models have given Apple one significant area to compete: privacy. However imperfect Apple is, they have rejected the tracking that predicates Google and Facebook’s business models.

In recent years, Apple have made a point of introducing privacy measures that highlight tracking to users to users and make it easy to opt-out of tracking.

These changes have had an outsize impact on the surveillance industry. For instance, SparkPost estimated that Mail Privacy Protection would impact the tracking of “30–40% of a recipient’s user list” – that means 30–40% of people in a mailing list, email funnel and other email types would be protected from spy pixels.

In another example, Apple introduced App Tracking Transparency in iOS 14.5 – a feature that forced app developers to ask users if they want to be tracked. Initial opt-in was incredibly low and, as of April 2022, this figure has only risen to 25%. In other words, 75% of users don’t want to be tracked.

Fighting adtech

Of course, Facebook, Google and the adtech industry fight these changes tooth-and-nail. They present themselves as the champions of small business and claim that Apple only make these changes to benefit their own advertising channels.

But – quelle surprise – this isn’t the whole truth.

From Amnesty International:

...a poll of leaders of small and medium-sized businesses in the two countries revealed 75% believed tracking-based advertising undermines peoples’ privacy and other human rights.

A total of 69% of business owners surveyed said that while they were uncomfortable with Facebook and Google’s influence, they felt they had no option but to advertise with them due to their dominance of the industry.

Talk about a duopoly.

In the UK, 99.9% of all businesses are small businesses. The numbers in France and Germany wouldn’t have to be anywhere near this and these percentages would still be significant.

In another example, an Amazon/Google-funded group claimed to represent thousands of U.S. small businesses:

When POLITICO contacted 70 of those businesses, 61 said they were not members of the group and many added that they were not familiar with the organization.

One business owner said:

I signed up for what looks like a webinar and now it seems like they’re using my name like I’m for their policies

This use and association was hidden in the terms and conditions:

In response to questions about the membership directory, 3C said all the businesses listed there had signed up for membership by agreeing to “terms and conditions” at the bottom of forms that state their name would be used in a membership directory.

Totally on-brand.

Competition

On the competition side, Apple will soon be fighting the case to enable privacy-protecting features in Germany.

As John Gruber writes:

The notion that if a company has built a business model on top of privacy-invasive surveillance advertising, they have a right to continue doing so, seems to have taken particular root in Germany.

I’ll go back to my analogy: it’s like pawn shops suing to keep the police from cracking down on a wave of burglaries.

One of the arguments the adtech industry makes goes something like this:

These privacy changes only impact third-party app developers. Apple benefit by blocking this tracking and don’t apply this definition to themselves or their own products: they can use the data they collect to target users in their own ads business.

But the difference between data acquired through engagement with a single company (e.g. Apple) and that acquired through sharing with third-parties (e.g. data collected through Facebook’s iOS app, sent back to Facebook to use in other contexts) is precisely the definition of tracking as outlined by the W3C:

Tracking is the collection of data regarding a particular user's activity across multiple distinct contexts and the retention, use, or sharing of data derived from that activity outside the context in which it occurred. A context is a set of resources that are controlled by the same party or jointly controlled by a set of parties.

In other words: if a user’s data is shared to a third-party app developer (e.g. Facebook) and then used to target them, that is tracking. Apple can use that data for targeting without it being considered ‘tracking’ as they haven’t shared that data with any third-parties.

As it happens, Apple recently demonstrated that App Store ads performed better with personalisation turned off. They could go all-in on contextual ads and put this argument to bed once and for all.

3. Data inaccuracy

It is becoming increasingly clear that the data organisations and marketers have come to rely on is inaccurate.

What sort of data are we talking about? All sorts, as it turns out:

Data for ad targeting

From Augustine Fou:

Studies have shown that these inferences are inaccurate, if not completely wrong. For example, a 2019 study showed that a single targeting parameter, gender, derived from anonymous website visitation patterns was only 42% accurate, worse than random. If you did no targeting at all, and just did "spray and pray" with your digital ads, you'd at least hit one of the genders 50% of the time. When two parameters were taken into account -- age and gender -- the accuracy dropped as low as 12%. That's like 9 times out of 10, those targeting parameters were wrong. And advertisers paid extra to make their digital marketing worse, not better.

From Subprime Attention Crisis:

...the accuracy [of data profiles used for advertising] was often extremely poor. The most accurate sets still featured inaccuracies about 10% of consumers, with the worst having nearly 85% of the data about consumers wrong.

Platform over-attribution/misreporting

From the Wall Street Journal:

Big ad buyers and marketers are upset with Facebook after learning the tech giant vastly overestimated average viewing time for video ads on its platform for two years.

Facebook disclosed in a post on its “Advertiser Help Center” that its metric for the average time users spent watching videos was artificially inflated because it was only factoring in video views of more than three seconds.

...the earlier counting method likely overestimated average time spent watching videos by between 60% and 80%

Ad fraud

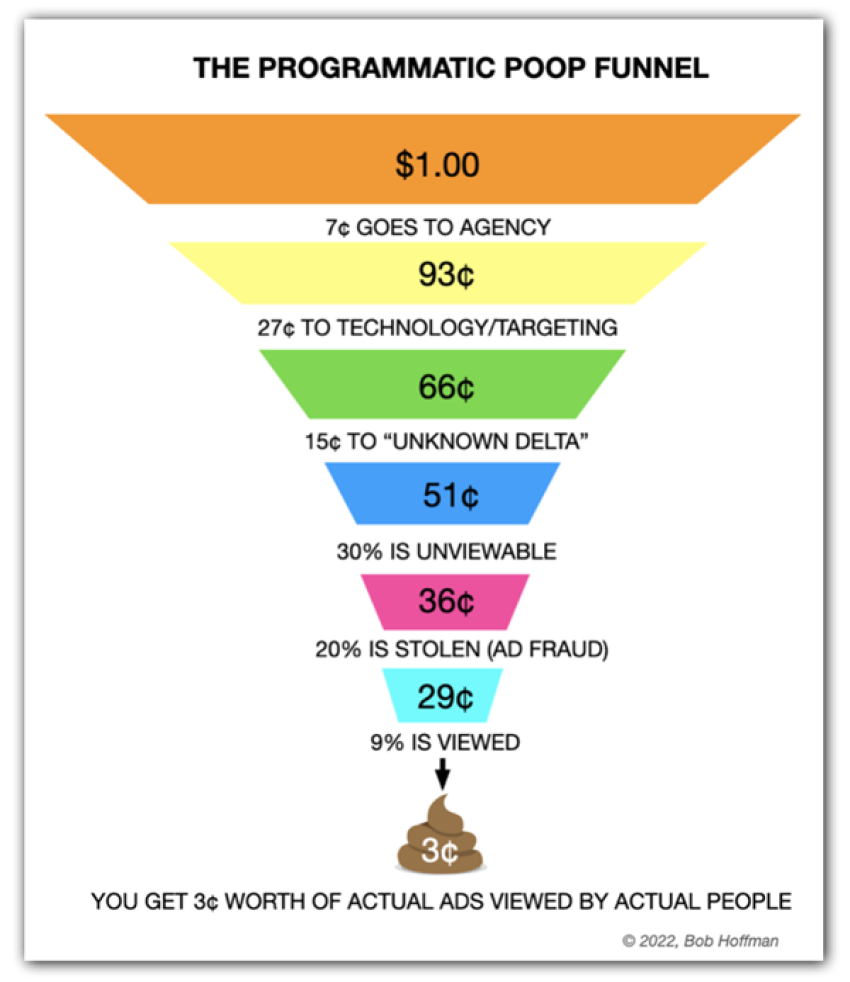

From Bob Hoffman:

This graph shows how 20% of each dollar that makes it to actual ads – not the agency, platform, “unknown delta” or unviewable – is stolen through ad fraud (bots, most likely).

To the advertiser, those clicks look real but they’re bots: they’ll never convert.

Tracker blocking

Just under 43% of internet users have an adblocker installed. Between adblockers and browsers that block Google Analytics by default, website data is likely missing a significant segment of our traffic.

There is an argument that analytics can be about aggregate data and there is truth to that. But if a business never sees traffic from a cohort that uses adblockers, tracker-blocking browsers or blocks spy pixels in emails, they’re permanently missing data – aggregate or otherwise – from users that take active measures to protect their privacy.

Taking steps to go privacy-first and review the metrics we value gives us less in-depth data to work with, but more high-level data across a wider range of users.

It’s also an opportunity to reassess how data-driven ‘best practices’ are used in an organsation and reduce instances of incomplete data influencing poor business decisions.

Email open rates are powered by embedded pixels that report all sorts of data when an email is opened. Email clients protect users from this tracking in one of two ways:

Open the email immediately on the recipient’s behalf. This will show as an open, even though the recipient hasn’t read it.

Block all images from loading by default. This will show as an unread email, even if the recipient has read it.

So how do we know if an email has been read? We don’t*.

(* unless the email is tracking clicks and that is factored into the rate: a method used predominantly in plain-text emails)

Changing tracking narratives

From Jeremy Keith:

We shouldn’t stop tracking users because it’s inaccurate. We should stop stop tracking users because it’s wrong.

This is absolutely true. But the inaccuracy of data could be the argument to shift the perspective of business owners, marketers and clients (who often fund this stuff, lest we forget).

Marketing and privacy are often pitched as being at odds with each other, but this is largely due to how data-driven marketing has become. If we can’t see the data for a marketing method, does that mean it’s ineffective?

From Atomic Habits:

Measurement is only useful when it guides you and adds context to a larger picture, not when it consumes you. Each number is simply one piece of feedback in the overall system.

In our data-driven world, we tend to overvalue numbers and undervalue anything ephemeral, soft or difficult to quantify. We mistakenly think the factors we can measure are the only factors that exist.

But just because you can measure something, doesn’t mean it’s the most important thing. And just because you can’t measure something, doesn’t mean it’s not important at all.

It is said that it’s difficult to make someone see something when their job relies on them not seeing it. But at some point, clients and businesses should start asking about the accuracy of the data and whether this is the best use of their marketing budget.

4. Ethical conflicts

As general awareness increases around the harms of tracking in the real world, so does awareness about the ethical conflicts of using these tools for marketing.

As businesses and organisations increasingly seek to leave the world slightly better than they found it, it’s not uncommon for them to have a started mission or purpose. In many cases, the use of surveillance tech would be in direct conflict with this.

For instance, over 11,500 tonnes of CO2 are produced every month by the cookies that power surveillance advertising. How does that align with organisations with sustainability at the heart of their mission?

Some companies have already taken action because of ethical conflicts. These include:

Starling Bank boycotted Meta over financial fraud on Facebook and Instagram

Lush quit Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat and TikTok because of the mental health impact of these apps on their target demographic

Patagonia stopped all paid advertising on Facebook “because they spread hate speech and misinformation about climate change and our democracy”

Then there are conflicts between our personal approaches to tracking and the users of our services. Many of us don’t want to be tracked, but are happy to force tracking on our customers and visitors.

The low opt-in of Apple’s in-app tracking – just 25% – would suggest that most of us choose not to be tracked when given a clear and simple choice. Why do we continue to surveil users when we know they don’t want to be tracked?

5. Privacy laws

The EU’s introduction of GDPR in 2018 set shockwaves through the internet. Initially viewed as a data concern limited to Europe, the world eventually realised that these laws applied to companies and websites with any European visitors or customers.

Even in countries that have limited data protection rights, or are seeking to strip existing ones (read: the UK), businesses still need to comply with the relevant laws of their visitors/customers. Instead of complying with two, three or four sets of regulations, the happy path may be for businesses to comply with the strictest law from the outset.

Additionally, we’re only just starting to see rulings that enforce the Schrems II judgement from June 2020. Both Google Analytics and Google Fonts have been ruled illegal on the back of the Schrems II case.

The implications of these rulings are significant, especially given how reliant the internet is on predominantly US-based content delivery networks (CDNs). However it’s clear that more rulings like this can be expected and there’s an opportunity for organisations to get ahead of this by considering their choice of tools from this angle.

And we shouldn’t forget that the online advertising industry’s trade body, IAB Europe, was found to have violated GDPR through its “Transparency and Consent Framework”.

The consent popup system known as the “Transparency & Consent Framework” (TCF) is on 80% of the European internet. The tracking industry claimed it was a measure to comply with the GDPR. Today, GDPR enforcers ruled that this consent spam has, in fact, deprived hundreds of millions of Europeans of their fundamental rights.

The decision affects the advertising arms of Google, Microsoft and Amazon. All of the data collected through the TCF had to be deleted.

6. Software and services

With awaress of privacy concerns growing in both the general population and among business owners, software developers and service providers have started to take note. Privacy-focused software has always existed, but the range has expanded greatly over the past few years, especially for software aimed at businesses.

With that in mind, it’s never been easier to find an alternative and switch to software that has a privacy edge. Below Radar’s Resources area is filled with options across a wide range of software types including analytics, email, newsletters and more.

Wrapping up

Whatever the reason for changing, there are business benefits to moving towards privacy-respecting marketing models. For instance, organisations that adopt this approach may be able to:

Boost trust among customers/users

More closely align marketing strategies with core organisational goals

Improve the experience of using their services

Reduce litigation risks

Build sustainable marketing methods that don’t rely on adtech’s algorithms

Save on expensive surveillance ads or spend that money on other marketing methods

We’ve already seen how some businesses are starting to take action, and a growing number are joining Below Radar, too.

Whatever the real or perceived costs of doing business in a privacy-conscious way, we’re headed towards a place that’s more privacy-focused, not less.

Organisations will have to look to more privacy-respecting marketing at some point. That might be because they realise there’s an ethical conflict, a data gap, inaccurate analytics or they’re forced to comply with data laws.

The effects of these factors might take some time to come through, but they are coming. For businesses who want to get ahead of the curve, privacy’s time is now.

Date

26th Jun, 2022